What is the place of work, technique and technology in art?

This is traditionally an annoying question for the philosopher, who is too well aware of the common roots of art and technique in techné (τέχνη) and of the difficulty of really telling (analyzing) them apart. On the contrary, the question is not so annoying for the artist, who has always done whatever work has appeared necessary with whatever techniques and technologies have been available, so that the artwork could be. As we shall see, especially in contemporary art s/he has also often put work into work, in all senses of the word. While the difference between creative art and instrumental work is unclear, there seems to be a general agreement that work is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of art: art needs work but this is not enough, art is something else, something more, something better. But what?

In what follows, I will try to shed new light on the problem by looking at it through the prism of robotic art that often deals explicitly with it – robotic art meaning art that uses different kinds of cybernetic autonomous systems, including artistic artificial intelligence, generative art and algorithmic art. What happens to artistic work when it is taken over by a robot that assumes a part of physical work, like for example the act of painting in So Kanno and Takahiro Yamaguchi’s Senseless drawing bot (2011)? What happens when the robot is an algorithm that takes over aspects of artistic thinking, such as the conception of the dome of Jean Nouvel’s Louvre in Abu Dhabi? Do art robots destroy artistic skills? or on the contrary require new kinds of know-how? Or are they the artwork? Do they work for the artist, with her/him, or as part of a bigger association of „actants“ around the work? Can the art robot be creative and if it can, what is creation?

In an automated society such as ours it is not surprising to see artistic robots and algorithms swarming everywhere. For instance, in Paris alone in the summer of 2018, I encountered many of them in several extraordinary exhibitions and manifestations, including Coder le monde. Mutations/Créations at the Centre Pompidou, ManiFeste 2018 at IRCAM, and Artistes et robots at the Grand Palais. I want to pay homage to these events because they inspired some of the reflections presented in this text, as well as many of its examples. However, my aim is not to present new tendencies of the art world, rather to interrogate art robots in general.

Two works can help to frame the issue. One of them is an experimental concert from 1997 in which the same pianist performed three Bach-like inventions, one of which was composed by J. S. Bach himself, another one by a contemporary composer Steve Larson, and the third one by the computer program EMI (Experiments in Musical Intelligence) designed by David Cope, himself a composer working at the University of California Santa Cruz. When asked which one of the inventions was composed by whom, the audience was mistaken all along, concluding that Mr. Larson’s work was made by the computer, EMI’s work was genuine Bach, and Bach’s work by the contemporary composer. Recently the historian Yuval Noah Harari made this experiment famous by quoting it in his book Homo Deus as an example of computers that appear to supplant the artist. (Harari 2017, 328-9) Of course one can also ask if Bach’s music is too regular for our ears, or if the contemporary public believes it to be so.

The other work is titled Pockets of Space and had its premiere on 23 June 2018 at the Centre Pompidou. It is a multi-sensorial immersive artwork consisting of Natascha Barrett’s music and OpenEndedGroup’s (Marc Dowie and Paul Kaiser) abstract video images that were generated in real time. The public encountered the work sitting on the floor in a vast dark space surrounded by an Ambisonic sound system (64 loudspeakers installed all over the space) and by a projected 3D video image. The sound-image-scape appears very abstract, like plunging into the structure of some unknown matter that could evoke microscopic cells or atoms, or perhaps macroscopic galaxies. Only at the very end did the image became a recognizable human-scale place, but by then, even a recognizable image appeared so synthetic and abstract that the general impression remained one of extreme abstraction. By way of illustration, at the same occasion was Ryoji Ikeda’s Continuum and Data.tron (figure 1), also immersive sound-image-scapes, but these were made of black and white square rules running over entire walls (that’s my idea of a “mind”) and of loud rustling sounds and infrasounds (that’s my idea of how electricity “sounds”).

It does not make sense to try to identify such immersive spaces. They are not imitations of natural places or of human-made works of art, but on the contrary, works that could only exist because of the algorithms that generate them. Maybe it would be possible to imitate them with painting, film, and a symphonic orchestra, but the working process would be long and fastidious, and the result probably clumsy. These works truly exist because they are generated and run by algorithms. Here, the question is not one of imitation (of Bach or some other master) but of the creation of something unprecedented. These examples show that the robot artists appear deceptive if they only imitate the human artist’s work, and that the core of their “art” is elsewhere. But where? The robot may well be the mirror of the artistic work, but it shows something to the artist because it is a distorting mirror that actually shows him/her another reality, from which s/he is separated by an “uncanny valley”.[ps2id id=’fn1-btn‘ target=“/]1

What are robots doing in art? To start with, they certainly reflect the omnipresence of robots in contemporary society – for today robots are everywhere. Most of the time, they are not visible as such, and if they are, they rarely look like the humanoid androids presented in science fiction. Instead, they do the invisible work that makes our world-go-round, like the industrial robots that work at the assembly lines of factories and the digital bots that organize and operate an ever-increasing part of today’s business and society. The main societal function of robots is precisely work: they represent a skilled workforce that does not need rest nor a salary. In this situation, it is natural to think that what robots do in art is taking over a part of the raw artistic work so that the artist can concentrate on creation, understood as conception. In this sense, a composer can let a computer produce “synthetic” sound that the composer can then organise “manually” into a composition. But art is never as simple: when the art robot works, it doesn’t necessarily liberate the artist from work, but on the contrary makes him/her ask what work is, and the answer appears more complicated than one might expect.

But how do artists see robots? It goes without saying that robots were born in imagination long before being fabricated in reality. The oldest imaginary robots known to us are literary representations of anthropomorphic beings made by the best of artisan-artists in order to show their superior skill – which is proven precisely by the fact that the creature works. Since the very beginning, the question of the robot is thus associated to the twin problem of work and creation. For instance, already in the Iliad, the divine master-smith Hephaestus had servants made of gold, fashioned like living girls and attending swiftly to their master (Book 18, 368-467). Later Greek stories describe Galatea, who was an ivory statue built by Pygmalion, and Pandora (figure 2), who was a woman made of clay by the order of Zeus, both of which were then miraculously animated. In the Bible, Psalms 139 tells how God fashioned the human body in the secrecy of the earth, out of the unformed matter of the lowest parts of the earth. God’s act was then imitated by the mythical Rabbi who shaped the Golem out of dirt, and the Rabbi was later imitated for instance by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, who assembled his monster out of dead body parts. Since the beginning, the creation of an animated artificial human being has appeared as the nec plus ultra of human science, art and craft. Throughout the myth’s different variants, the human-like creature is to some extent the image of its maker, but nonetheless marked by an inevitable inferiority that finally marks the superiority of the creator over the creation. In the stories, the creator is a male artist-artisan with superior skill and knowledge. The creature is not an exact mirror image of the artist, but either an ugly, dim-witted vaguely masculine monster whose aim is to work for his creator, or a beautiful woman that the artist builds to help him and to keep him company. (Most of the time, the feminine robot, or fem-bot is a servant, although her work might mainly consist in the availability to the male gaze and his needs). It makes sense that the first real android (a knight) was constructed by the universal artist-engineer Leonardo da Vinci in 1495, but the Golden Age of automats started really in the 17th century in both Europe and Japan. The constructors of automats were the very best of artisans who surpassed simple craftsmanship and reached stunning ingenuity, if not outright creativity. The automats, in turn, were expected to work, also in the practical sense of doing something. They served tea, played chess, played music, and so on. This kind of an anthropomorphic robot servant is still one of the objectives of today’s robot constructors who work for instance on engineering hotel reception hostesses, but who actually appear to excel particularly at constructing sex robots. However, the sophistication of a real dancing doll, as imagined by E.T.A. Hoffmann in his Coppélia, is still an unreachable technical challenge that has yet to be impersonated by a living ballerina.

»Actually, what is truly incarnated in robotic industrial work is not a particular state of technological development but these particular social orders.«

In the 20th century, real androids remain rare masterpieces of craftsmanship, while functional industrial robots have proliferated everywhere. Industrial robots are purely and solely manifestations of superior workforce and skill. They are the logical conclusion of Taylorism, which first divided work into isolated gestures and then restrained each worker to one gesture only. From the point of view of human beings, this is how the skilled artisan gave way to the unskilled worker: while the artisan used tools, the worker was reduced to being a simple tool of the machine. The alienating and dehumanizing effects of modern industrial technology have been described in the mid 20th century especially by Martin Heidegger, Jacques Ellul and resumed a bit later by Gilbert Simondon in his On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. Sharing the general diagnosis of these authors, Western Marxists attributed the dehumanizing effect of modern industrial work differently: they saw it less as a consequence of the new technological systems as such, but of the social orders of both capitalism and real socialism that use technology in dehumanizing ways. Actually, what is truly incarnated in robotic industrial work is not a particular state of technological development but these particular social orders. These considerations can also be found in literature. For instance, it is not by chance that some Italian futurists celebrated in a single gesture fascism and the industrial merging of man and machine. On the contrary, the machinization of man was criticized with irony already in 1921 in the Czech writer Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R. (where the word “robot” actually comes from: Čapek’s brother made the word up from the Czech word robota, which means the serfs’ forced labour, figure 3). The play depicts the creation of artificial people, roboti, so that they could work for human beings. First the roboti are happy with their condition, but later they rebel against it and almost destroy the human race. The play reads as a critique of total war and industrialization as well as a premonitory warning against the totalitarian project of the education-fabrication of the New Man. Čapek’s idea – the creation of artificial human beings who end up surpassing their masters and revolting against them – is one of the main narratives of the robot stories of the first half of the 20th century, and remains still today. On the one hand, the robots‘ sad condition is a warning against industrial capitalism and totalitarianism. On the other hand, their threat is a warning against the destruction of human competences by the introduction of machines that take over work, skill and knowledge.

In these reflections from the first half of the 20th century, writers criticize their time’s official doctrine’s blind celebration of technological progress by pointing at the Faustian ambivalence of modern technology. The popular figure of the robot turning against its maker impersonates the human being’s own ambivalence who is at the same time the fabulous inventor of a new world, and the destroyer of existing beauty and intelligence. More often than not, robot stories fundamentally defend a more delicate humanity against brutal machinic modernity. Similarly, the criticism of technology was also a concrete political movement. In industry, the so-called luddites had protested against industrialization already in the beginning of the 19th century by breaking the machines that stole their work. One can identify an analogical movement in art in the beginning of the 20th century, when many artists (and their public!) fought against the introduction of mechanical machines into art, claiming that photography and film are not art but only mechanical reproduction of reality, or tricks to produce cheap illusions.

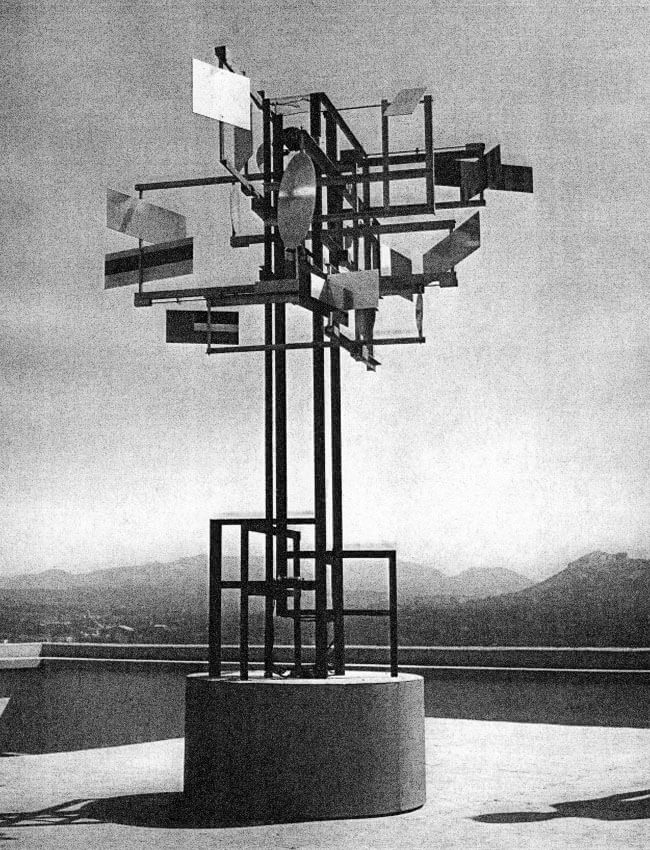

In these stories, artists do not use robots but represent them, and the robots are hardly anything more than metaphors of the human condition. They build the robot as a mirror of humanity that is at the same time superior to ordinary human beings (stronger, faster, eventually superintelligent) and inferior to them (it is stupid and heartless essentially because it is a slave). When real robots start to make apparitions on the art scene starting from the 1950’s, they turn out to be very different from these representations. Like industrial robots, the new artistic robots are mechanical things made of motors, wheels, straps, repetitive gestures and even automatic movement. They do not appear frightening, but actually rather joyous and endearing, for they look like big toys that pursue a relentless mindless activity with utmost application and sincerity. The first cybernetic sculpture is Nicolas Schöffer’s CYSP 1 (1956), which is a kinetic sculpture that can move and turn its multicoloured plates in function of external stimuli. In its premiere it danced to Pierre Henry’s music with the dancers of Maurice Béjart’s company. Jean Tingelyi’s Méta-matics series, constructed since 1959, are mobile drawing machines consisting of motors, wheels, straps, pliers, and other mechanical parts that also look very machine-like. When a pen is attached to the machine’s arm and a paper posed in front of it, the machine draws pictures. In the Paris Biennale of 1959, Meta-matic n° 17 produced 40 000 drawings, each one of which is unique, for the machine is designed so as not to repeat itself. In the same playful, ironic vein, Raymond Queneau invented his Cent mille milliard de poèmes (1961), a book of poetry whose pages are cut in strips, each of which holds one line of the page-long sonnet, so that new pages can be recomposed by choosing the strips differently. With this book, everyone can compose as many perfect sonnets as they like, and according to Queneau this fruit of the „workshop of potential literature“ gives enough material for 100 000 000 years of reading 24 hours per day.

These works do not represent machines but put machines directly on stage where the robots produce art in a single ironical gesture that deconstructs both the productivist society and the art institution. Are the robots “just artists like any others”, like the art critic Lityin Malaw has suggested?[ps2id id=’fn2-btn‘ target=“/]2 Unlike the classical artisan-artist, these robots produce their works automatically and industrially. They mime industrial society’s obsession of productivity, but they also show the mindlessness of the frenzy of the production process. They also ironize the underlying ideology of production, for the movements of the machines only amount to piles of useless art products. It seems to me that these are not good enough to be framed, and that it is more fitting to consume them – for one doesn’t really watch Meta-matic n° 17’s drawings for themselves nor does one really meditate and re-read one of the One thousand billion poems, one just consumes them in passing. This is how these art robots seem to push to its conclusion Walter Benjamin’s famous idea of the “loss of aura” presented in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, but at the same time they affirm, together with Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in the Appendix of Anti-Œedipus, that the disappearance of the unique character of the “auratic” work of art is a joyous event instead of a melancholy one. The art products are very different from the accomplished unique beauty and perfection of classical art. CYSP 1’s dance or Meta-matic n° 17’s drawings are not very beautiful, more like a clumsy child’s lurches and scribblings.

»While producing a practically infinite amount of works, the robots celebrate useless productivity.«

However, the robot art products are not necessarily trivial. Today, it is also possible to construct robot-artists whose works strive for beauty, like for instance the drawings of Patrick Tresset’s Human Study n° 2.d La Grande Vanité au corbeau et au renard (2004-2017). This work involves a drawing desk and a stand on which a still life model of a human skull with a stuffed fox and a stuffed raven have been posed. They are being drawn by an automatic system that consists in a single machine eye and a machine hand holding a bic pen. The drawings are beautiful – they continue Tresset’s (figure 4) own style before he lost his capacity to draw because of a disease. Nonetheless, because the machine produces them so untiringly, the individual drawings are lost in their endless proliferation. They are not identical, tiny differences of direction change the pictures, but at the same time none of them is unique either, but only an element of a series. The sublime infinity of the unique masterpiece has given way to the bad infinity of endless repetition of slightly different but equivalent works. While producing a practically infinite amount of works, the robots celebrate useless productivity. The robots produce works wantonly and aimlessly; they function without function, or with a meaningless function. Because their products are meaningless, the attention of the spectator turns towards the pure functioning itself.

This is how the art robots attract attention to the activity of making art instead of the resulting works. Encouraged to figure out the mechanism and the principles of functioning of the robot, the spectator is invited to ask what artistic creation really is. Ever since Kant’s Critique of judgment, most theoreticians of art would say that artistic creativity is mimesis as poiesis and not mimesis as imitation; and that art is therefore creation, not repetition. Great art does not follow a rule, it creates a rule. The art robot holds in front of the artist a distorting mirror in which s/he can seek his/her distinctive difference: the mirror shows that while both the artist and the robot make art, the artist made the rule (program) that the robot can only follow (execute). But it is easier to state such a distinction than to hold to it in practice. Of course artists follow some rules, too, even when they mean to challenge them somehow, and many important works of art are really perspicacious variations of a given principle, like, say, Bach’s Goldberg variations. On the other hand, the works produced by the artist robots are not exactly identical, either, but they incorporate aleatorical elements that make the difference in the identical series. The robot’s free will is aleatorics, that industrials robots are expected to exclude but that art robots are on the contrary expected to generate. This is why the art robots’ works are not only copies, but they also have some elements of creation.

This is why many contemporary artists have chosen an opposite path (provided by more advanced technology, of course). Instead of underlining the way in which a machine follows a code, they want to liberate unforeseen possibilities of the complex code, eventually by opening it to more or less aleatory external stimuli. Suddenly, the code is not a restriction of creation anymore, but on the contrary its condition. For example, Leonel Moura’s Robot art (2017) is a work consisting of a swarm of small robots, each of which holds a felt pen and draws lines on a white surface with walls (the walls are there so that the robots would not fall down from their working table). The paintings are not predetermined by the artist but they result from the stochastic and stigmergic action of the robots themselves.[ps2id id=’fn3-btn‘ target=“/]3 The robots do not have a leader but they are auto-organized, and it is impossible to determine in advance the results of their interaction. If Moura’s robots interact with one another, other works interact with spectators. Edmond Couchot’s and Michel Bret’s Les Pissenlits (1990-2017) is a digital image of huge dandelions projected on the walls of a room. In the room there is also a sensor on which the spectators can blow, and when they do, the fluffy balls of the dandelions blow in all directions. Each blow is unique, and in this sense the work reorganises itself in countless ways in reaction to external impulses. Surely the works are still limited to possibilities of the code and the dispositif. But at the same time, what the spectator sees is a unique moment that would on the one hand not exist without the dispositive, but that is on the other hand not exactly foreseeable in the code, either. The code is a virtual possibility, not a causal reason of the work.

Internet intensifies the possibilities of liberating a code to find things that we would never find by ourselves. Grégory Chatonski has explored the possibilities of algorithms that look for material at the Internet in several works, for instance in Le Rêve des machines which is based on a archival collection of dreams that the algorithm illustrates from images found on the Internet. The work functions like big data research: it filters enormous masses of data that a human being could never process alone, and collates the results in a way that reveals unexpected patterns of reality. Of course, the reality discovered by a big data program or even by an artificial intelligence might be unexpected, but this does not necessarily mean that it is interesting, intelligent or morally solid for that matter. This is manifested for example in Oscar Sharp’s Sunspring (2018), which is a short science fiction film written by the robot AI Benjamin, a neural network of LSMT that has learned the art of storytelling by analysing numerous science fiction series and their texts. The result is surrealistic, meaning nothing but hilariously mimicking and involuntarily comicking the genre.

The emancipated AIs and algorithms promise to liberate art from the human perspective as the sole starting point of artistic production. The artist renounces his/her control of the work willingly and gives him/her/self to the deployment of the work, and this is why s/he appears to question the anthropocentric starting point of the work. This gives these works a “posthuman” tint: indeed they reveal other contents, other forms, other realities. Sometimes they are stunningly beautiful, like Pockets of Space, Pissenlits or Extra-Natural: they generate extraordinary unforeseeable spaces, like another nature beyond our old ageing Earth, a true alter-world where genuine alter-creatures may dwell. But sometimes they border on pure silliness, such as the world generated in Sunspring, and give the impression of mainly revealing the unnameable unconsciousness of humankind that might not be revealed without this abandon to non-knowledge, but which is nonetheless perfectly human. Indeed, technological art can challenge traditional anthropocentrism by generating nonexistent artificial paradises, but can it ever create a truly nonhuman reality if it is, after all, programmed by humans?

Now, is artificial intelligence about to become the creative machine that robot-building artists have both dreamed about and feared? Following thinkers like N. Katherine Hayles and Bernard Stiegler, I argue that technology and even the so-called artificial intelligence is not really a superior intelligence: it is a different one. Even when it is equipped by self-learning mechanisms, a technological entity does not think (and this is why artificial intelligence is more properly called machine learning). It has two other characteristics of intelligence, instead: it remembers all (while we forget and by doing so make place for new discoveries) and it calculates well (while we are slow and make mistakes, and this is why we like to imagine other ways of solving problems). It makes little sense to ask which approach is more intelligent because these are quite incommensurable types of intelligence. Instead, it is important to see how they need one another. The same incommensurability can be found in the question concerning the machine’s capacity creation. When human beings have tried to understand their own creativity, they have come up with a number of different answers. For instance, creativity has been understood as a capacity to produce beautiful things, or as the capacity to invent new rules of production, or as the receptivity to unheard-of events. As soon as such definitions have taken shape, clever artist-engineers have sought for ways of reproducing similar functions in machines and especially computers. So they have built machines that produce beautiful things that take aleatoric changes in account, and that explore unforeseeable virtual possibilities. None of such functions are “really creative”, for the machines only do what they are instructed to do. But at the same time, each one of them shows why the definition of human creativity was insufficient, for it was possible to simulate it with a simple machine.

»Work is his/her own intimate alterity and alienation that s/he constantly tries to overcome: humanity is essentially defined by this intimate dialectics between work and creation.«

The real lesson of robotic art is therefore not the distinction between creative human beings and working machines. It is not even the capacity of the human being to create machines that enhance his creativity, which also requires a lot of human work. It is the necessity to rethink human existence in such a way that his/her technological supplements are really an integral part of his/her humanity. The robots are not his/her Others, they are him/her/self externalized in things and then again internalized in his/her activity. This means that even without anything like a robot, the human being is already a being that works and uses technological supplements to do it. Work is his/her own intimate alterity and alienation that s/he constantly tries to overcome: humanity is essentially defined by this intimate dialectics between work and creation.

More essential than telling the difference between humans and machines is finally learning to co-operate with machines in a satisfactory way. The aim is not to use machines but to work with them. This means, firstly, that to do art, humans generally need some technical virtuosity, some mastery of instruments and theories. Some artists, like for instance Xenakis, have been accomplished engineers whose work also helps engineers outside of the world of art. Some others, like Tómas Saraceno, recognise that they do not have all skills that they need, and therefore work in collaboration with scientists, engineers and other specialists. Works themselves can be co-operative, like Pockets of space, and of course almost every piece of theater and film. Technics is not the Other of humanity, it is just one element of an assembly that makes art happen. This is also why artistic work tells us something about the future of work in the society as a whole. Art cannot say what the future of work will be, but it can show what are the utopias available for us today are, which include collaborative creative works that combine both elements of the human and the machine.

Header image credit: Nicolas Schöffer, CYSP 1, 1956